< Return to index

BACK TO REDFERN

Autonomy and the ‘Middle E’ in relation to Aboriginal health

Ernest Hunter *

Introduction: William Redfern

The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in

the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function. One

should, for example, be able to see that things are hopeless and yet be

determined to make them otherwise. [F. Scott Fitzgerald cited by Rescher

1987]

William Redfern was born around 1774. What is contentious – it may have been

Trowbridge in Wiltshire, it may also have been Canada. He passed the examination of

the Company or Surgeons in January 1797, days later joining HMS Standard in the

North Sea Fleet based at The Nore in the Thames estuary. The country was newly at

war, isolated from Europe and socially volatile. The economic crisis compounded the

appalling conditions in the Navy, with the Channel Fleet at Spithead near Portsmouth,

and the Fleet at The Nore petitioning the Admiralty for relief. Since the reign of Charles

the First such acts had been regarded as treason (Rodger 1997). Negotiations resolved

the situation at Spithead, but events spiralled out of control at The Nore with Fleet ships

blockading the Thames. Ultimately the mutineers surrendered and were courtmartialled,

Redfern being sentenced to death. Some 36 were hanged but Redfern’s

sentence was commuted to transportation and he arrived at Port Jackson in the convict

transport Minorca on 14 December 1801.

Pardoned on Norfolk Island in 1803, Redfern returned to Port Jackson and was

involved in farming and business, some minor political intrigues, a vaccination

campaign, and was appointed assistant colonial surgeon at the General Hospital where

he met Governor Macquarie in 1810. Redfern had come a long way since surviving

transportation. The death rate in the First Fleet was one in seventeen. In the Second

Fleet it soared to one in four. Between 1801 an 1814 it fell from one in ten to one in 46.

However, in 1814 Macquarie called on Redfern after 88 deaths in three transports,

Three Bees, Surrey and General Hewitt, and his report brought about changes in

hygiene, diet, access to fresh air, medical assistance, and independent medical

monitoring, measures credited with reducing mortality from 1 in 30 to 1 in 120 (Hughes

1988). In December of that year he was invited to join “a committee for conducting and

directing all the affairs connected [with] ameliorating the very wretched State of the

Aborigines” (Jones 1999a).

We do not know much about his involvement with Aboriginal affairs, but he was

instrumental in improving the rights of emancipists, petitioning the king to restore full

rights to those pardoned (Torney 2001). He was a key driver in the formation of an

obstetric ward in the Female Factory, in bringing a modicum of humanity to the care of

the mentally ill at the Castle Hill Asylum, and was a foundation director of the Bank of

New South Wales. He had his share of controversy, accused of using public medicines

in private practice and financial impropriety, which brought him into court on charges of

defamation and, later, assault of an editor of the Sydney Gazette. He left Australia in

1828 to take his eldest son, William Lachlan Macquarie Redfern, to Edinburgh where

he was visited by Mrs Macquarie who commented that he was keeping questionable

company, gambling and borrowing money, including from her. He died there, of causes

unknown, on 17 July 1833 (Jones 1999b).

The other Redfern

Redfern was not the first doctor to be concerned about the welfare of the Aboriginal

populations around Port Jackson. Inga Clendinnen’s Dancing with Strangers provides

an insightful picture of Surgeon-General John White who arrived with the First Fleet

and whose unorthodox approaches inspired confidence and trust (Clendinnen 2003).

But there are other connections to Aboriginal affairs. The area of central Sydney that

bears his name is on a property that had belonged to Redfern. In the late nineteenth

century it housed employees at the Eveleigh Railway Workshops. Aboriginal movement

into the area began in the 1920s, and it was a centre of political activism by the 1960s.

In 1972 plans for demolition were opposed by Indigenous leaders, the Builders

Labourers Federation and others.

In the following year, the Aboriginal Housing Company purchased a series of row

houses to become the first urban land-rights claim in Australia. The early 1970s also

saw the first Aboriginal legal and medical services, both in Redfern.

As the 2004 riots affirm, Redfern remains a site of protest and symbol of injustice. It

was fitting that Paul Keating launched the Year for Indigenous People there on 10

December 1992 with a speech that Noel Pearson stated “was and continues to be the

seminal moment and expression of European Australian acknowledgement of grievous

inhumanity to the Indigenes of this land” (Pearson 2002). Keating (2005) said:

And, I say, the starting point might be to recognise that the problem starts

with us non-Aboriginal Australians. It begins, I think, with that act of

recognition. Recognition that it was we who did the dispossessing. We took

the traditional lands and smashed the traditional way of life. We brought

the diseases. The alcohol. We committed the murders. We took the

children from their mothers. We practised discrimination and exclusion. It

was our ignorance and our prejudice. And our failure to imagine these

things being done to us. With some noble exceptions, we failed to make

the most basic human response and enter into their hearts and minds. We

failed to ask – how would I feel if this was done to me? As a consequence,

we failed to see that what we were doing degraded all of us.

Towards a just society: professional ‘responsibility’

Keating’s acknowledgement is also a statement of hope and justice. “If we can imagine

the injustice” he emphasised, “we can imagine its opposite. And we can have justice”.

Justice and hope (or optimism) in relation to Indigenous health is what I will consider in

this talk. My reason for doing so is that last year I attended a conference1 – Towards a

Just Society: Issues in Law and Medicine – where Professor George Hampel presented

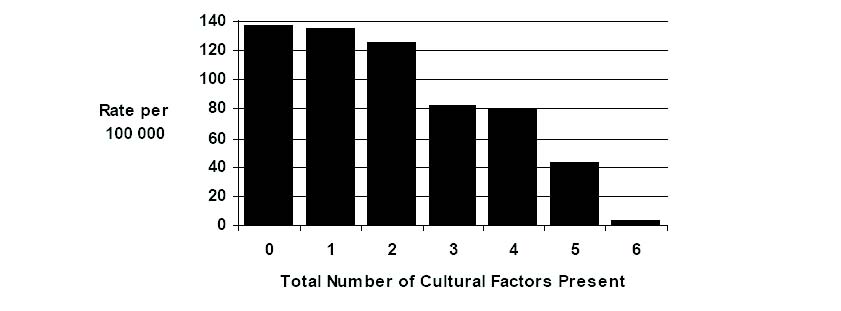

a figure and a challenge. The figure was the letter ‘E’ repeated three times and

superimposed (Figure 1).

He explained that ‘E’ stood for ethics and that in terms of our respective professions the

smallest ‘e’ represents ‘professional ethics’ or codes of conduct – What is the

responsibility of the individual as a professional? The largest, outermost ‘E’, represents

those principles of universal ethics which are often incorporated into ‘mission

statements’ – What are the responsibilities to humanity and, indeed, the biosphere?2

The challenge presented was to unpack the ‘middle E’ which is somewhere between

prescribed and proscribed behaviours, and ultimate principles. The ‘middle E’ is about

responsibilities rather than ideals or praxis.

Figure 1. The ‘Three E’s’

There is a precedent; the American

Institute of Architects identifies:

canons, which are broad principles of

conduct; ethical standards which are

goals towards which professionals

should aspire; roles of conduct,

violation of which results in

disciplinary proceedings (Lichtenberg

1996).

But medicine and law view ‘rights’

differently – law privileges negative

rights – the right not to be subject to

arbitrary arrest, to refuse treatment,

and so on. By contrast, medicine

privileges positive rights – the right to

make informed decisions, to receive

treatment, to best practice and, controversially, to health. Regardless, the consensus

was that medicine and law should strive for a just society. Does this suggest that

doctors and lawyers are, in some way, ethically ‘privileged’?

A decade ago I answered this question in the negative. Around that time I wrote about

three Jewish doctors who survived Auschwitz (Hunter 1997). I had already written on

the role of German professionals, particularly anthropologists and psychiatrists, in

developing the ideology of medical and race-based murder (Hunter 1993a). In relation

to the Jewish doctors (one was a public health doctor, one a psychiatrist and the last a

forensic pathologist), I was exploring how professional identity was used in the service

of survival and I drew on the typology – perpetrator, victim and bystander – which I

have used in considering the roles of health-professionals in relation to Indigenous

Australians (Hunter 2001). The third Auschwitz survivor was Miklos Nyiszli, a

Hungarian forensic pathologist who became personal assistant to Josef Mengele.

Nyiszli’s (1973) book, Auschwitz: A doctor’s eye-witness account, is chilling, but the

critical issue is that he was profoundly compromised by his association with Mengele

and by his conflict in reconciling doctor as murderer. Indeed, psychoanalyst Bruno

Bettleheim, a pre-war concentration camp survivor, commented in the foreword to a

reprinting, that Nyiszli “… volunteered to become a tool of the SS to stay alive” and that

he repeatedly referred “to his work as a doctor, though he worked as the assistant of a

vicious criminal”.

Bettleheim is scathing of Nyiszli. But is this reasonable? I thought not as this means

judging Nyiszli primarily as a doctor rather than a victim, essentially blaming him for

surviving. However, it also presumes a greater capacity for ethical behaviour or

altruism of doctors – even under extreme adversity. I won’t go into my rejection of this

position, but, in doing so I was considering medical identity as a personal attribute. I

realise now that I had confused, as I believe had Bettleheim, the practitioner and the

profession. Indeed, in the death camp the latter ceased to exist save as a parody,

either in the rationalisation of murder or in the service of survival.

Clearly, the training or position of a medical professional does not necessarily confer

ethical competencies. However (the extreme circumstances of Nyiszli aside) by

accepting the responsibilities and privileges associated with those roles in terms of

public support and trust, and the asymmetrical relationships of power that characterises

the doctor-patient relationship, the medical profession does have responsibilities, which

include ensuring that individual members of the profession are aware of and responsive

to their obligations regarding ethical practice. This demands ensuring access to the

means (information, debate, guidance…) that supports reflection on the ethical

implications of professional practice and the ability to make informed judgements, both

in working with individual patients and in terms of the wider social implications of

professional practice.

Towards a just society: Aboriginal health

Thus, I contend that medical practitioners do have a responsibility to strive towards a

just society and to make judgements based on an awareness of the social implications

of professional activities. In this paper I explore this issue as a medical professional

working in an area of stark inequalities that challenge any sense of Australia as a just

society – Indigenous health.

I will start with three vignettes. The first was a meeting in Normanton in 2005 to discuss

mental health with Indigenous residents of the Gulf, where services are poor. Trying to

be optimistic, I outlined the growth of mental health services in Cape York.

But I was silenced when a man from Mornington Island commented ironically: “things

must be a lot better in those Cape communities”. Of course, they are not, and I was

reminded of one troubled community in which an audit of mental health-related service

activities was undertaken following a suicide in 2003. Twenty-two providers were noted

across seven agencies – for a community of 1200 souls. The problem was not lack of

services, and the solution was not more of the same.

The second vignette relates to a meeting in 2005 in Lockhart River attended by Jim

Varghese, previously Director-General of Education, and the mayors of Lockhart and

Napranum. The topic was education, an attendee noting that only in the last two years

had the first Lockhart student completed secondary school. This was attributed to a

boarding school support program that recently had lost funding. However, the non-

Indigenous school principal commented that, save for a small group of high achievers,

it was inappropriate to send youth to boarding school as they would be homesick, fail

academically and miss out on cultural activities. He added that to make the local

curriculum more ‘relevant’ for those returning, cultural education was emphasised and

that each student had a small farm plot to tend.

The response was telling. Those who spoke up made it clear that they wanted their

children to get an education that gave real opportunities. They did not see this as

possible locally and stated that supporting children at boarding school was their priority.

The Mayor of Napranum related that the school in his community had been closed and

that the children now attended the mainstream school in Weipa. This was, he added,

appropriate, as the standards of teaching, expectations of students and outcomes were

dismal in the community by comparison to the mainstream. His focus was on

outcomes.

The final vignette stems from meeting the United States Surgeon-General, David

Sacher, in Alice Springs in the late 1990s. He had asked the then Health Minister,

Michael Wooldridge, to give him exposure to Indigenous issues. Wooldridge took him

to Central Australian communities where the backdrop included pot-bellied children

with runny noses, scabies and cans of petrol; where the legacy of abuse and violence

was etched into battered faces and deformed limbs, and where there were few

surviving elderly. At one point Dr Sacher commented: “you don’t have a health problem

here – you have an education problem”. I don’t know what Wooldridge’s response was;

he had his own ideas and in the 1998 Redfern Oration stated: “The truth is we do know

what can fix Aboriginal health” (Wooldridge 1988). Manifestly, that knowledge was not

sufficient.

It might be argued that the issues described reflect injustice and that, invoking the

categorical imperative, as rational and autonomous beings who are also privileged and

empowered professionals, we should be guided by moral precepts to rectify the

situation. However, that is the ‘Big E’ – it does resolve competing motivations and

values on the ground. These vignettes also touch on the four deontological principles

commonly identified in discussions of medical ethics – autonomy, beneficence,

nonmaleficence and justice3 (Bloch and Chodoff 1981; Gillon 1985; Beauchamp and

Childress 1994; Coady and Bloch 1996). The Aboriginal man in Normanton was

pointing out that outcomes were less evident than good intentions. He might have

added that without outcomes, creating dependency on external services is harmful,

undermining family and community roles (Trudgen 2000). This raises questions about

beneficence and non-maleficence as well as autonomy, all of which were also at issue

in the Lockhart education debate. But this last was also about opportunity and the

freedoms that brings. Freedom as equitable opportunity is increasingly invoked,

including by certain Indigenous leaders (Gerard 2005; Stannard 2005). Finally, David

Sacher’s comment in Central Australia involved failures with respect to all four –

manifest injustice, impotent beneficence, maleficence of neglect, and autonomy as

illusion of choice and control of destiny. It was also a warning regarding medical hubris.

Of course, we are aware that real improvement will require more than health sector

investment (Wilkinson and Marmot 2003). The major reductions in Indigenous perinatal

and infant mortality through the 1970s and 1980s came about primarily because of the

extension of basic services. However, the perinatal and infant mortality rates remain

two and three times higher, respectively, for Indigenous versus non-Indigenous

populations (Trewin and Madden 2005). Indeed, recent reliable data demonstrates that

the Indigenous: non-Indigenous perinatal mortalities have increased over the last two

decades being worse in remote areas (Fremantle et al. 2006). While service access is

important, this persisting gap reflects social determinants (Booth and Carroll 2005).

Is it reasonable to expect heath professionals to take this on? What do our professional

bodies say? While the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists’

(2004) Code of Ethics deals almost exclusively with practice, the College also has

‘ethical guidelines’ on a range of topics, Number 11 being “principles and guidelines for

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health” (RANZCP 1999). Item 4.1 states:

Health professionals need to be aware that interventions within the arena

of Indigenous health necessarily have political implications. Involvement in

this area of professional practice often involves challenging government

policy and community attitudes which have the potential to impact

negatively on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social, emotional,

cultural and spiritual wellbeing.

The AMA (2005:4) Position Statement on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health

affirms “That Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders will not achieve equal

health outcomes until their economic, educational and social disadvantages have been

eliminated”.

‘Overcoming disadvantage’ is also central to current Commonwealth policy in

Indigenous affairs (Anon. 2005). However, as Aiden Ridgeway (cited by Arabena

2005:14) has stated:

The classification of Indigenous peoples as simply ‘disadvantaged’ does

not address the real structural and systematic barriers that have

contributed to the situation we are now in. We are all being co-opted into

over simplified debates about our needs which is based on language

benign in appearance but loaded in meaning.

That ‘loaded meaning’ includes understandings of citizenship that have been debated

since the demise of assimilation, specifically equality, equal rights and sameness,

versus difference, Indigenous rights and uniqueness (Sanders 1998; Anon. 1998;

Arabena 2005), which, in turn, informs arguments regarding separatism versus

incorporation into the mainstream (Altman 2005), and Indigenous citizenship and rights

as a collective, versus as individuals, which has become particularly salient in relation

to the wider Australian economic and welfare systems (Sanders 1998; Rowse 1998).

The ‘loaded meaning’ also relates to the tension between privileging autonomy versus

prioritising outcomes.4

To return to the Lockhart River vignette: Providing opportunity by sending children to

boarding school, it might be argued, smacks of paternalism. The same could be said

for alcohol management plans and Shared Responsibility Agreements which justify

restrictions in ‘autonomy’ by recourse to a utilitarian conception of justice. However, in

relation to ‘opportunity’ health and education are rights that share special features that

set them apart, best grasped using a contractarian, more specifically a Rawlsian,

egalitarian, or ‘fair go’ view of justice (Rawls 1999). In this, justice is served through

equality of opportunity, for which health and education are unique as fundamental

building blocks, placing them in a special ‘rights’ category (Daniels 1985).

Furthermore, as strategic ‘social goods’, additional responsibilities apply in relation to

disadvantaged groups. From a Rawlsian, egalitarian view, health and education

resources should be distributed so as to ensure access to the normal range of

opportunities available in that society. That this is not the case in relation to Indigenous

education was fore-grounded in Bob Collins’ (1999) report on Indigenous education,

which stimulated the AMA (2001:2) Position Statement on The Links Between Health

and Education for Indigenous Australian Children; this recommends that “service

delivery in health and education to Indigenous children should be seamless, both in

theory and in practice”. Dream on.

Rights and opportunities

Health and education are powerfully related (Crombie et al. 2005), particularly maternal

education and child survival in the Third World (LeVine et al. 1994). I will give three

examples across the lifespan for Indigenous Australians. First, in the late 1980s, my

brother and I surveyed a random sample of six hundred Aboriginal Kimberley residents

aged fifteen to eighty years, including physical and mental health status, and

demographic and social factors (Smith et al. 1992a; Smith et al. 1992b; Hunter et al.

1992; Hall et al. 1993; Hall et al. 1994). After thirteen years, an intra-sample analysis of

social variables (Calver et al. 2005) included: income; incarceration; childhood

environment; traditional language fluency; ‘Christian’ identification; and, level of

schooling. Morbidity outcomes were all causes, alcohol-related, and injury-/poisoning

related first hospital admissions. The most consistent finding was that having some

secondary schooling demonstrated a strong negative relationship with all three

(Wiltshire and Hunter 2004). Second, the Western Australian Child Health Survey

(Zubrick et al. 2004), the most detailed and comprehensive survey of Indigenous

children and families to date, identified that higher maternal education is associated

with lower prevalence of substance use among children. Third, an analysis of 672

births to Indigenous women in Brisbane between 1996 and 1999 revealed a significant

relationship between maternal education and intra-uterine growth retardation. Even

adjusted for alcohol, tobacco and drug use, the difference in rates between those with

Year 12 compared to those with less than Year 10 schooling was almost three-fold

(Craig 2000). These findings should be no surprise.

Clearly, social determinants are critical in relation to Indigenous health, and education

is a key determinant with particular status from a social justice perspective. Further,

both health and education are necessary preconditions of fair equality of opportunity.

From the policy documents cited, this is a field in which medical professions and

professionals should be engaged – But how? Should elimination of health differentials

be both goal and justification – a utilitarian and paternalistic approach? Or, should we

be guided by principles – of autonomy and social justice?

Does this boil down to a tension between an ‘ends justify means’ paternalistic

interpretation of beneficence, and autonomy as means and ends? In reality, these

principles are not necessarily incompatible, and in relation to clinical practice

Beauchamp and Childress (1994:272) have commented that:

The debate between proponents of the autonomy model and the

proponents of the beneficence model … has often been confused by a

failure to distinguish between a principle of beneficence that competes with

a principle of respect for autonomy and a principle of beneficence that

incorporates the patient’s autonomy.

While this relates to patients’ rights, it is relevant to current Indigenous affairs policy,

which appears to have shifted from the latter to the former. Regardless, while

“beneficence that incorporates autonomy” might be an ideal, on the ground there

remains a vigorous debate between those prioritising autonomy or self-determination

(however conceptualised), and those calling for ‘real outcomes’ – whatever it takes.

Remote ‘liabilities’

Of course, Indigenous Australia is a diverse tapestry. While I worked briefly in Redfern,

my career has been in remote Indigenous Australia, largely in communities whose

history, particularly in Cape York, is of concentration in isolation, and that have been

called “outback ghettos” (Brock 1993). It has been argued that the structure and

governance of such settings is primarily driven by bureaucratic expedience to facilitate

collective engagement with the welfare system and mechanisms for ‘consultation’ with

individuals whose authority lies in a ‘democratic’ process that has often been divisive

and has marginalised traditional authority and landedness (Macdonald 2001). I recall a

conversation in one such community with an Aboriginal nurse and her South African

husband who commented: “You’ve been more successful at apartheid here than in

South Africa”. His point was that while civil and political rights had been won by

Indigenous Australians before the dismantling of apartheid, social rights had not, at

least in ex-mission communities set up away from the economic mainstream from

which, for most, there was no escape save for brief sojourns to the parks of Cairns – or

jail. It might be argued that this is a matter of ‘choice’. But, deprived of enabling

education or skills, choice is an illusion. While the disadvantage of urban Indigenous

communities is real, albeit less ‘visible’, remote communities confront particular

difficulties. This has long been recognised in policy, and informed the setting up of

Community Development Employment Projects (CDEP) (Sanders 1998).

Unfortunately, the situation is now often compounded by reliance on non-Indigenous

intermediaries with the skills to manage escalating administrative and technical

demands (Palmer 2005).

According to some, such settings are ‘liabilities’ and it has been suggested that

government policy, implicitly, incorporates “categories of competence” (Arabena 2005),

being (1) competent Indigenous people who reside in urban areas and who should

have no access to Indigenous specific funding; (2) those who live in remote areas and

lack competence due to disadvantage-related circumstances and should be helped; (3)

those who continue to choose to live in disadvantaged communities and who choose to

lack competence, that is, those who cannot be helped at all.

This is powerful language, now echoed in the media with headlines such as on page 1

of The Australian – “Aborigines choose welfare over work” (McKenna 2006). ‘Choice’

can be similarly invoked in relation to the burden of chronic disease, with ‘lifestyle’ used

in such a way that the context of social disadvantage is reduced to irresponsibility

(Hertzman et al. 1994).

Thus, they are not only the least ‘competent’, they are least ‘deserving’. From an

economic perspective, persistent dependence in remote settings seems incontestable.

Indeed, Jon Altman, staunch critic of economic rationalist arguments regarding the

viability of remote Indigenous communities, had admitted that in these settings, even

with a “hybrid economy” incorporating “non-monetized” inputs, “so-called ‘welfare

dependence’, will not decline markedly”.

Altman (2005:42) went on to state, however

, that “there is a strong moral, political and

economic argument for using a different nomenclature for such state support. It could

be defined as regional fiscal subvention”.

While I understand this argument and appreciate the importance of non-stigmatising

language, it is not JUST about economic viability, OR “unrecognised productive

activity”. It is about what it means, at a personal and group level, to be denied real

choice and control in what is, regardless of location, a globalised world.

Health and social change: suicide

I will now consider a health issue related to these psychosocial consequences –

Aboriginal suicide. In Queensland the Indigenous suicide rate for 1999 to 2001 was

fifty-six percent higher than for the State as a whole, with the rate for young males aged

15 to 24 years 3.5 times higher. Some eighty-three percent of Indigenous suicides were

less than 35 years of age (42% for the state) with ninety percent of these deaths by

hanging (De Leo and Heller 2004). However, suicide is unevenly distributed. The total

number of Indigenous suicides increased nearly four-fold in the period 1992 to 1996

(accounted for by an increase in young male hanging deaths), a disproportionate

number occurring in the north of the state where three communities contributed to this

excess at different times, overlapping ‘waves’ of suicides suggesting a condition of

community risk varying by location and time (Hunter et al 2001).

Aboriginal suicide was rare before the late 1980s, before which it tended to be men in

their third and fourth decades in non-remote settings (Hunter 1993b). That changed

with the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (Johnston 1991), which

investigated deaths in detention, one-third of which were suicide. The intense media

focus informed constructions of hanging that fore-grounded oppression, associating

‘meaningfulness’ with hanging. Since then, suicide has increased in the wider

Aboriginal population, the highest rates being teenage and young adult males, now

increasingly in remote populations (Davidson 2003), sometimes taking on ‘traditional’

meanings (Parker 1999; Parker and Ben-Tovim 2002; McCoy 2004). But, the patterns

continue to change. In the first months of 2004, four children aged 12 and 13 died by

hanging in four communities in Far North Queensland. To explain these changes I will

use trend data from the Kimberley and Cape York.

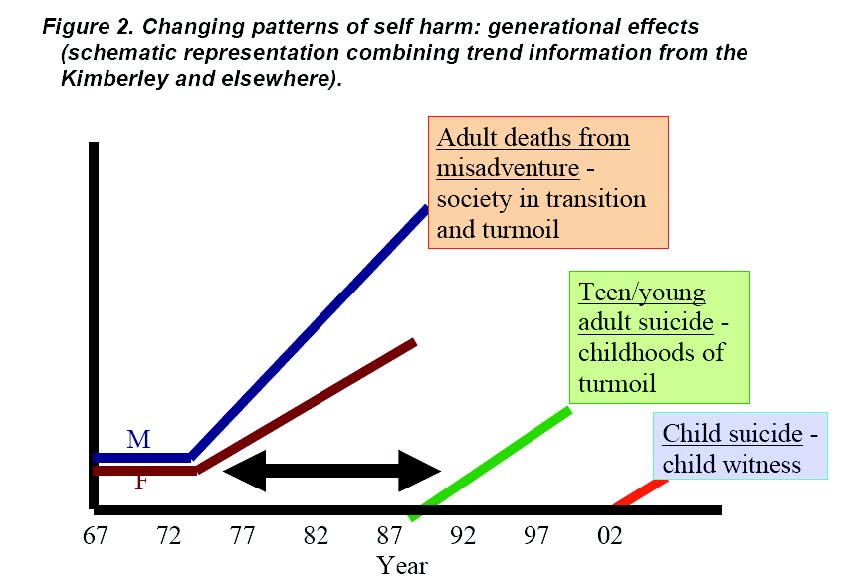

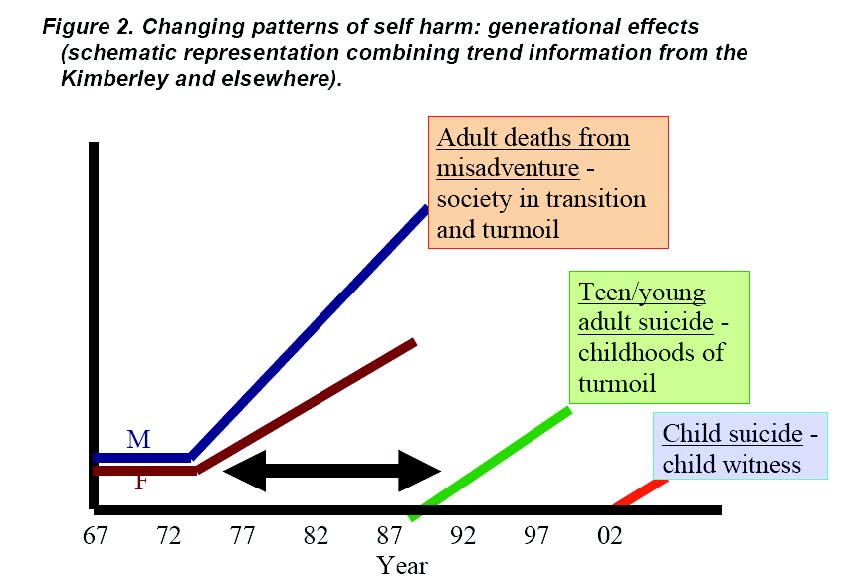

Across Indigenous Australia the 1970s ushered in turbulent social change that has

been described as ‘deregulation’ (Hunter 1999). This most immediately impacted young

adults for whom onerous controls were lifted, with entry into the cash economy through

welfare, and unrestricted access to alcohol. However, while discriminatory legislation

was revoked, other barriers, less tangible but robust, persisted, what has been called

“cultural exclusion” (Brody 1966). The social and behavioural consequences were

evident in the Kimberley with a dramatic increase in deaths from external causes

(accidents, motor vehicle accidents and homicide, largely being of young adults) from

two to four percent of deaths in the fifteen years to 1971, to fifteen percent of female

and twenty-five percent of male deaths in the fifteen years following (Hunter 1993b).

Suicide did not increase until the late 1980s – some fifteen years delayed (one suicide

in the 1960s, three in the 1970s, twenty-one in the 1980s and forty-six in the 1990s).

These were teenagers and young adults – the children of that earlier generation

exposed, as young adults and new parents, to deregulation and its social

consequences. The young suicides were from the first generation to have been raised

in that environment of unremitting instability. Not only were they at risk of self-harm but

also petrol-sniffing, sexual abuse (as victims and perpetrators) and self-destructive

confrontations with increasingly reactionary authorities (Hunter in press).

Self-harm is no longer uncommon and its visibility in remote communities exposes

children – from other children wandering the streets with cans of petrol, to violence to

self and others, to threats, acts and representations of suicide. Indeed, among the child

hanging-deaths described earlier, all had been exposed. They belong to the first

generation in which many children’s early development includes exposure to the threat

or act of self-annihilation (Figure 2).

Key mediator: child development

The effects of social change on patterns of self-harm are mediated by their impacts on

early development, which is critical for realising health and educational potential – that

is, for optimal opportunity in life. The effects of prenatal environmental factors (including

social adversity) on the development of diseases including diabetes and hypertension

later in life is well known (Gluckman et al. 2005). Similarly, from conception through

infancy, neurological, cognitive, affective and social development is an interactive

process between a phase-sensitive evolving system and the environment (Schore

1994; Keating and Hertzman 1999).

This includes the ‘embedding’ of experience in biology through processes of selective

activation and neural sculpting, and the transmission of emotional and social capacities

through what has been called “reciprocal, co-regulated emotional interactions”

(Greenspan and Shanker 2004). Extensive developmental neurobiology research now

also informs our understanding of social gradients in health (Kelly et al. 1997). Indeed,

it has been noted that “the effects of these early developmental processes can be

observed in the health and competence of populations” (Keating and Miller 1999:220).

Longitudinal studies demonstrate that failure to provide for early phase specific needs

is consequential for the later development of serious emotional and behavioural

problems, including violence (Tremblay 1999; Hertzman and Power 2003; Schore

2003). Ultimately, as Keating and Hertzman (1999) have noted:

… over time, the physiological aspects of less than optimal

neurophysiological development, chronic stress and its psychological

impacts, a sense of powerlessness and alienation, and a “social support”

network made up of others who have been similarly marginalized will

create a vicious cycle with short-term implications for education, criminality,

drug use, and teen pregnancy, and with long-term implications for the

quality of working life, social support, chronic disease in midlife, and

degenerative conditions in late life.

This sounds like the Aboriginal communities in which I work, and I am acutely aware of

the levels of stress therein. That stress impacts health is well known (McEwen and

Norton 2004) as it is that stress in early life, including pregnancy, can have longterm

consequences for emotional development and capacities to respond to stressors later

in life (Cynader and Frost 1999). Although Indigenous data are limited, the Western

Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey (Zubrick et al. 2005) demonstrated elevated

risk for clinically significant emotional and behavioural disorders for Aboriginal children

aged 4 to 11 (26%) and 12 to 17 (21%) compared to non-Indigenous peers (17 and

13% respectively). Among associated social factors were poor-quality parenting, poor

family functioning, being raised by a sole parent or a non-parental carer, a history of

parental forcible separation, and the number of life stress events in the prior twelve

months (22% of children were living in families with seven or more life stresses).

So, stress is common in Indigenous families and associated with negative childhood

outcomes. One mediating pathway is prenatal exposure to stress hormones (Cynader

and Frost 1999; Weinstock 2004). Studies from the Kimberley have shown levels of

glucocorticoid excretion during normal life higher than any other researched population,

and of catecholamines also high by world standards (Schmitt et al. 1995; Schmitt et al.

1998). Sequential measures of urinary and salivary cortisol (Schmitt et al in press)

revealed a pattern that the researchers associated with the stress of the welfare

economy cycles in resource-poor communities where ‘demand sharing’ (Peterson

1993; Macdonald 2000, 2001) pressures are intense. Among those affected are young

women and the pregnancies they carry. So, even prenatally the stress of

disadvantaged communities impacts neurodevelopment – this before considering other

factors that inform poor perinatal outcomes, including the neurotoxic effects of alcohol,

for which there is now evidence of substantially higher levels of harm among Aboriginal

compared to non-Indigenous children (Bhatia and Anderson 1995; O’Leary 2002).

How, then, do we conceptualise the capacity to exercise informed and healthful

‘choice’?5

But – children are resilient. Indeed, this is one of the key findings of the Kauai

Longitudinal Study which followed a cohort of 698 children born on that Hawaiian island

in 1955 (Werner 1989). That research showed that for children at risk a key resilience

factor is supportive relationships (Power and Hertzman 1999). In reviewing outcomes

at age 40, Werner (2004:492) noted that poor outcomes were associated with:

… prolonged exposure to parental alcoholism and/or mental illness –

especially for the men. Individuals who had been born small for gestational

age and those who received a diagnosis of mental retardation in childhood

had a higher incidence of serious health problems in adulthood, including

serious depression. They also had higher mortality rates. … Men and

women who had encountered more stressful events in childhood reported

more health problems at age 40 than those who had encountered fewer

losses and less disruption in their family during the first decade of life.

Some decades ago I worked in disadvantaged native Hawaiian communities. I assure

you, circumstances are significantly harsher in remote Aboriginal Australia. Werner’s

study is repeatedly cited to emphasise the importance of a ‘good enough’ start to life.

This is equally or more critical in Indigenous Australia. While Aboriginal children are not

condemned to poor health and social outcomes, they are more at risk than their non-

Indigenous peers due to socio-environmental adversity, which also compromises those

factors that could support resilience – risk amplification.

Social justice and medicalised solutions

In terms of responses to the tragedy of Indigenous suicide, what is NOT being

addressed are the developmental precursors of risk. Instead, the focus has been on

discrete risk or group ‘trauma’. With respect to risk, this has been conceived narrowly

as risk of suicide rather than lifestyles of risk, leading to ‘treatment’-oriented

interventions – counsellors, life-promotion officers, early-intervention programs and so

on. The premise is that these are vulnerable young adults who need help. Other

approaches start from the premise that risk is a consequence of ‘trauma’, a concept

with currency in Aboriginal Australia since the ‘stolen generations’ were identified in the

1980s (Read 1981) and, particularly, since the release of the Human Rights and Equal

Opportunity Commission’s (1997) report on the removal of Indigenous children from

their families. This is an important issue that demands a brief digression.

The

Commission recommended a framework for reparation involving:

1. acknowledgment and an apology;

2. guarantees that human rights won’t be breached again;

3. restitution (or restoration);

4. rehabilitation; and

5. compensation.

Compensation is due for breaches of human rights. This is the big issue, adroitly

evaded by the Government through two mechanisms. First, by focusing attention on

then Prime Minister’s Howard’s refusal to apologise which, I contend, then Prime

Minister Paul Keating did in Redfern (Pearson 2002). The emotions unleashed in the

wider Australian public were powerful, but did more to sentimentalise symbols (Gaita

1999) than support understanding, and were unsustainable. Second, by emphasising

and medicalising consequential harm which, in thereby trivialising human rights

violations (Hunter 2002) is a form of denial (Hunter 1996).

I am not suggesting that medicalisation is necessarily harmful. Brady (2005:132) noted

that “For many Aborigines seeking solutions to their chronic health problems, better

and more thorough medicalisation is desired, not less”, the doctor’s status providing

authority and legitimation supporting decisions, for instance, to control drinking.6 This

brings me back to paternalism, as this might be considered an example of justified

paternalism, that is, a coercive intervention in relation to an informed, voluntary and

autonomous decision (to drink to excess) which is made in the best interest of the

patient. However there is a difference between acts of paternalism and “public and

institutional policies” of strong paternalism (Beauchamp and Childress 1994:282).

Brady’s use of medicalisation is consistent with an act of ‘justified paternalism’. While

subject to abuse, such acts are inevitable in medical practice. The medicalisation of

social injustice is another matter. Medicalisation operates through the “exercise of

institutionalised power” (Parker 2004), whereby the social context of disease is

diminished and/or social phenomena are subsumed within a hegemonic, biomedical

discourse (Filc 2004).7 In relation to ‘trauma’, the process was driven by political

expedience and supported through the health sector, with funding for grief and loss

counsellors the major response of the Commonwealth government. Subsequently,

‘grief and loss’ has come to represent both a psychological state (of distress) and a

symbol (of social injustice), with a parallel confusion in terms of ‘trauma’ with

intergenerational trauma also understood as both a state and a process (Hunter in

press).

What has disappeared is the breach of rights, replaced by grief, loss and trauma which,

because legitimacy is conferred by demonstrated harm, is articulated as depression,

anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder. Indeed, Christine Adams (2005:184) has

argued that “social distress and dissent are thus reduced to biological dysfunction and

psychological pathology for which short-term, politically-neutral technical solutions like

medication and counselling are deemed most appropriate”. With the past now made

present in disorders of mental health, Aboriginal Australians, Adams (2005:330)

anticipated, “may find it difficult to relinquish their now-medicalised melancholia as a

basis of political agency”. Ironically, the Commonwealth funds grief and loss

counsellors to address the mental health consequences of past policy, and lawyers

who vigorously resist personal or group claims on the basis of harm so caused.

I am not trying to minimize emotional pain but to problematize the obfuscation of

violation in a fog of medical disorders. If post-traumatic stress disorder or depression

signify violation, what does recovery signal? I am also not denying inter-generational

effects. The changing patterns of harm and self-harm over successive generations

identified earlier is one example. But, the mediating factor is developmental, specifically

the impact of the developmental milieu – from amniotic to family and social

environment – on neuro-psycho-social development.

Social transformations vs ‘modest but practical ways’

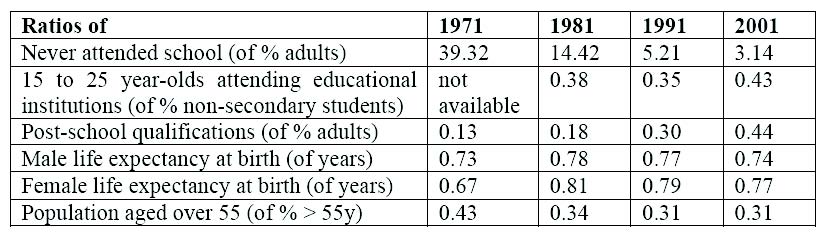

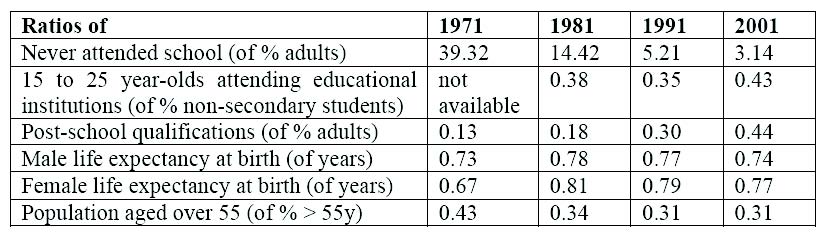

Earlier, I suggested that remote communities are particularly impacted. I will explore

this in more detail. A review of health and education outcome data for the period 1971

to 2001 shows that by comparison to non-Indigenous Australians, while Indigenous

health parameters have not improved significantly, there has been a dramatic increase

in participation in education (Table 1) (Altman et al. 2005).

Table 1: Ratio of Indigenous to non-Indigenous education and health

outcomes

1971 to 2001 (derived from Altman, Biddle and Hunter 2005)

Ratios of 1971 1981 1991 2001

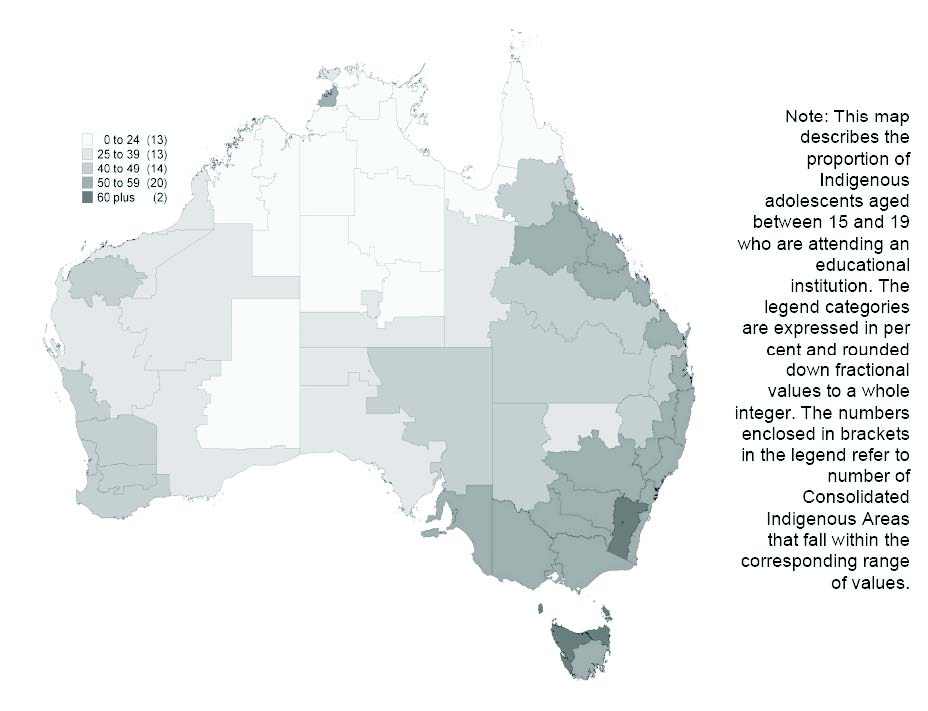

However, while education participation is a predictor of employment generally, that is

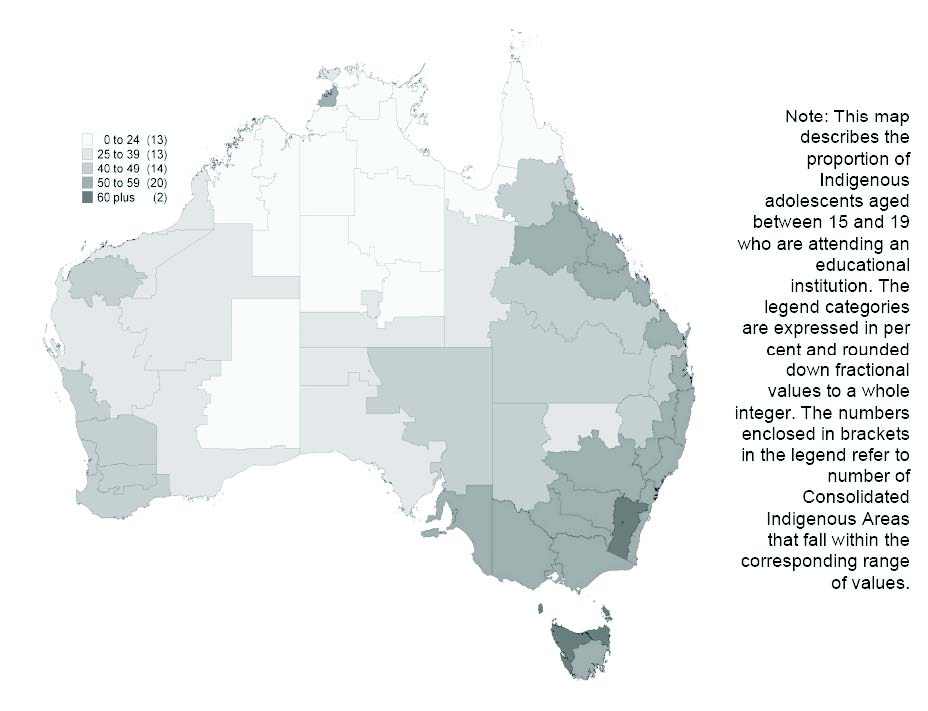

not the case in remote settings. Data from the 2001 census (Figure 3) reveals that

retention of Indigenous adolescents in the education system is much lower across

remote northern Australia, the predictors of poor participation being: limited education

access; domestic disruption; being Aboriginal rather than Torres Strait Islander; lack of

access to electronic resources; and with presence of the CDEP scheme (Biddle et al.

2004). The authors comment on the disadvantage for remote Indigenous Australians of

being isolated from the wider, globalised society.

Lest we be seduced by the aggregate improvement in attendance, the recently

released education report from the Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey

(Zubrick et al. 2006) shows that academic performance for Aboriginal children is

significantly below that for the State as a whole, and that this relates to: poorer

academic performance among parents; poorer attendance at school; and higher

proportions of Aboriginal children with emotional and behavioural difficulties.

Furthermore, while Western Australian absentee rates were less than in New Zealand

or the United States, rates were considerably higher for Aboriginal compared to Maori

or Native American children. This report concludes that there has been no obvious

progress in terms of outcomes over the last thirty years, that poor academic

performance is being passed down inter-generationally, and is set during early school

years. Finally, while physical health problems and poor nutrition clearly impact

education, they are not the major factors holding back the performance of Aboriginal

children in school.

Figure 3. Indigenous adolescents attending educational institutions,

2001 (from Biddle et al 2004).

Obviously, attendance is necessary but not sufficient to secure educational outcomes –

and outcomes remain poor. Exiting school does not improve the situation. For instance,

the Indigenous youth detention rate is some twenty times greater, nationally, than for

non-Indigenous young persons (Charlton and McKall 2004; HREOC 2005a).

Unemployment is common and more so in remote areas. Indeed, at a national level

Indigenous engagement in the workforce, as with education, has not shown significant

improvement over the last thirty years.

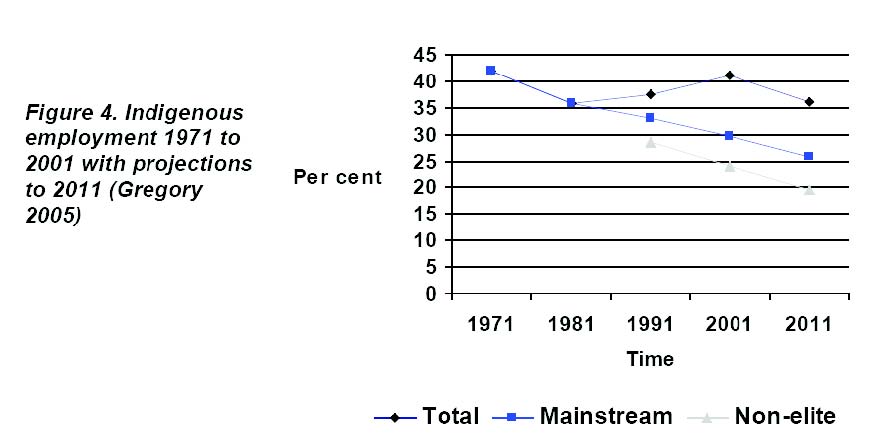

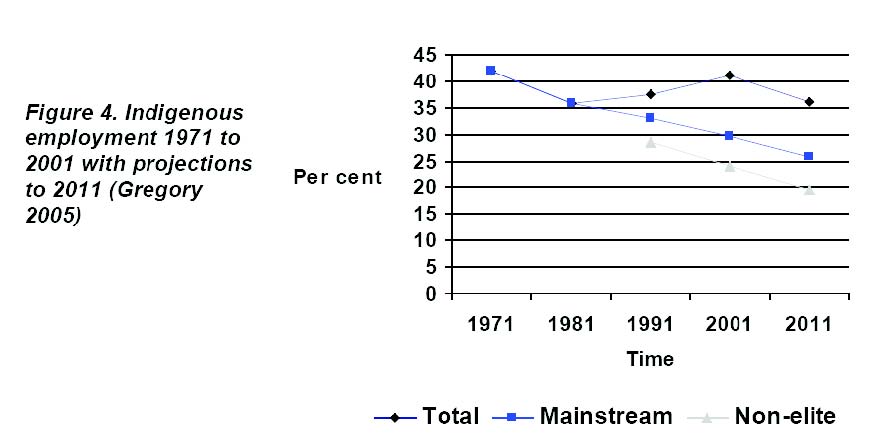

If CDEP is removed, employment has fallen, which is accentuated when considering

‘non-elite’ employment, that is, removing those Indigenous workers in the top thirtypercent

income-bracket nationally (Figure 4). This raises important and difficult

questions for remote communities – does CDEP constitute an economic lifeline where

there are no opportunities – or does it cement locational disadvantage by dissuading

engagement in education and the mainstream economy? (Gregory 2005). Probably

both. What I want to impress is that key indicators of disadvantage and determinants of

opportunity are not improving, and particularly compromise remote Indigenous

populations. I have avoided graphic anecdotes to exemplify the stress and turmoil

impacting these populations, but turmoil there is and it is not ‘here today and gone

tomorrow’. Without significant changes, it will be there for decades to come. That is,

unless, going back to Paul Keating’s Redfern speech, we can “imagine its opposite” and

make it happen.

Making it happen

So, how to ‘make it happen’? Well, that demands goals, and the means and motivation

to reach them. In terms of goals, while there may be debate about those chosen, key

indicators for overcoming Indigenous disadvantage have been developed, and health

and education are prominent (Anon. 2005). In terms of motivation, because health

professions have strategic influence over an area that is a precondition of equality of

opportunity, there is a responsibility to strive for a just society in which that is realised.

However, there is a circular cause-and-effect relationship between health and a just

society that involves more than semantics. How this is constructed has significant

implications for ‘making it happen’. For instance, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Tom Calma, has focused on Indigenous health

in the 2005 Social Justice Report, utilising a human-rights framework to inform

recommendations that foreground equitable access to effective primary care (HREOC

2005b). The report is powerful and persuasive – that is, to those motivated by human

rights. However, it can be argued that if the purpose is to harness public opinion and

galvanise political will, justice is less suasive than health. While poor school

attendance, unemployment and overcrowding may reflect disadvantage, for many

Australians they are also understood in terms of choice and this can be used for

political expedience – blaming the victim (Das 1994). By contrast, nobody would invoke

choice to explain dead babies and foreshortened lives.8

This has a further implication. Health and education are special ‘rights’ in terms of fair

equality of opportunity. Education is a key determinant of health status and, as

suggested by David Sacher, may be the critical factor in addressing the injustice in

which both are embedded. But, health may be a more suasive and potent political lever

– it contributes to all ‘rights’ and, more importantly, is manifest and measurable.

Indeed, health may provide the most powerful argument for investment in Indigenous

education as a necessary precondition of a just society that includes significant

improvements in the broad social determinants of health and wellbeing.

However, I am also mindful of Syme’s (1997:9) caution regarding being immobilised by

the task of social change: “If we really want to change the world we may have to begin

in more modest but practical ways”. Sustaining such modest but practical ways

demands challenging inertial fatalism (Hunter 2000), and nurturing optimism. So, how

does one remain optimistic? Well, there are three types of optimism (Rescher 1987).

First, actuality optimism – things are good, let’s ride the wave. This is manifestly not the

case. Second, tendency optimism or meliorism – things are getting better, let’s just

hang in there. Given the persistent Indigenous: non-Indigenous health gap in Australia

compared to New Zealand, Canada and the United States (Ring and Firman 1998;

Ring and Brown 2003; Lavoie 2004), this is questionable. However, Ian Ring9i has

made the point that this may be beginning to change and he emphasises the

importance of clinical best practice, for instance ACE (Angiotensin Converting Enzyme)

inhibitors, and end-stage renal disease (Thomas 2004, 2005). This is important and per

Syme it is practical, but it is also very modest.

Finally, prospect optimism – the future will be better contingent on suitable actions.

That is, effort will make a difference. This, I suggest, is our only basis for optimism. So,

how should that effort be directed? In terms of both modest but practical ways and

influencing social determinants, we need to consider whether this is driven by values,

such as social justice or autonomy, or by a utilitarian, ‘outcomes’ approach.

While the former appeals to our ethical sensibilities, there are examples of policies and

programs informed by wider-societal concerns for social justice which, in Indigenous

settings, have had untoward outcomes (Hunter 2006). Examples include welfare

support, royalties, revocation of prohibition, victim compensation, fostering autonomy

without capacity, and privileging customary legal defences. All of these are rights which

should not be revoked – but they are not unproblematic. This may also be extended to

certain ‘traditional’ practices (Sutton 2001, 2005) that “now exist under conditions that

differ significantly from those of the pre-colonial era” (Sutton 2001:140).10 Indeed, in

the face of “rhetoric about empowerment and self determination” (Sutton 2001), and the

continuing failures of Aboriginal affairs policy, particularly in relation to remote

communities, some informed and sympathetic commentators have called for a drastic

review of priorities including “artificially perpetuating ‘outback ghettoes’” and even

support for Indigenous service delivery (Sutton 2001). Basically – ‘whatever it takes’ –

paternalism in the service of outcomes.

Of course the same argument, invoking best interests and using the same indicators of

disadvantage, can rationalise conservative economic agendas (Hughes 2005). It is

then a short step, using entirely legal means within provisions of the Native Title Act, to

“develop and divide”, further ghettoising and impoverishing Aboriginal groups – as

happened to the traditional owners of Australia’s most resource rich real estate – the

Burrup peninsula in the Pilbara (George 2003).

Regardless, there are issues, such as education and the developmental vulnerabilities

associated with changing patterns of self-harm that involve vulnerable children’s

fundamental rights. In seeking to resolve the conflict between principles of autonomy

versus beneficent but paternalistic intervention, we might reflect on the position we

would adopt if foetal alcohol syndrome increased by fifty-fold in our neighbourhoods

(O’Leary 2002). Or if the majority of children who should be in high school were not.11

Or if notifications for gonorrhoea and chlamydia among junior high school children

increased one hundred-fold (Anon. 2001). Or if children were found hanged.

Autonomy, paternalism and the capacity to choose

I am not seeking to trivialise autonomy and underline its importance with research on

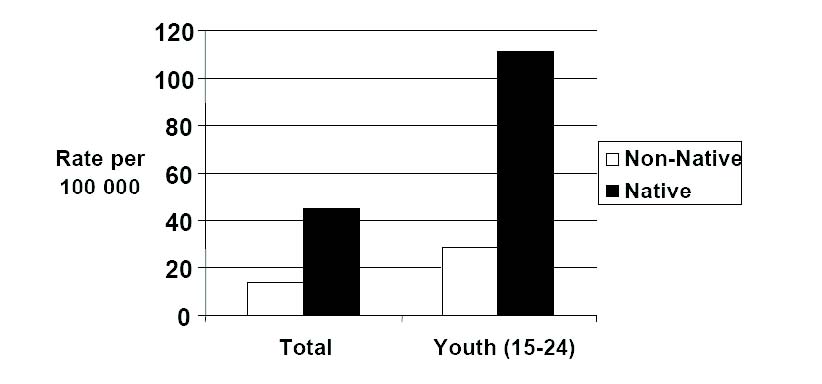

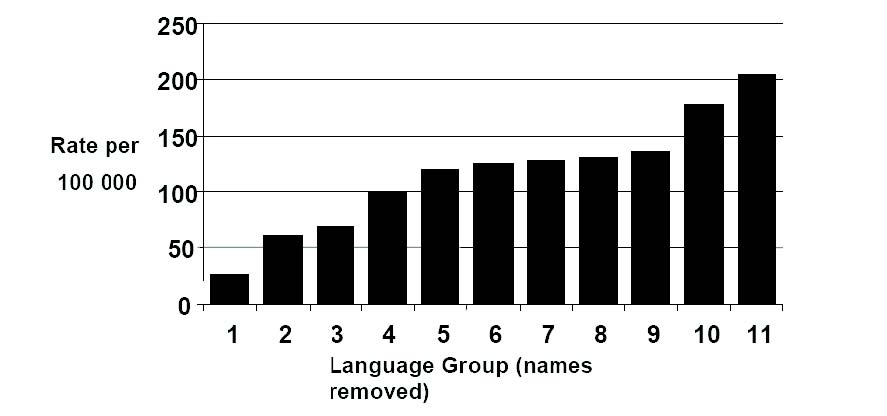

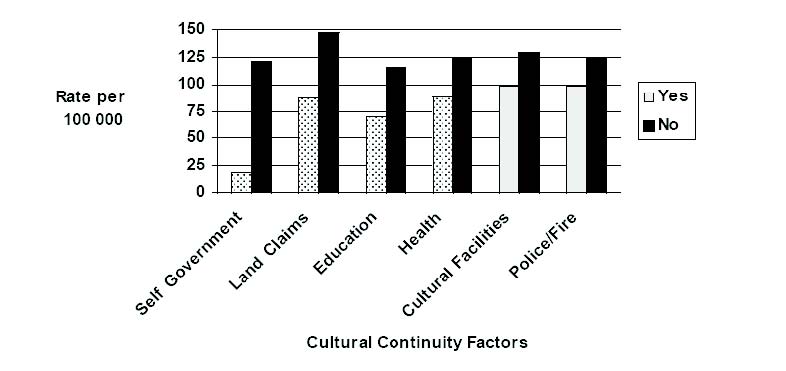

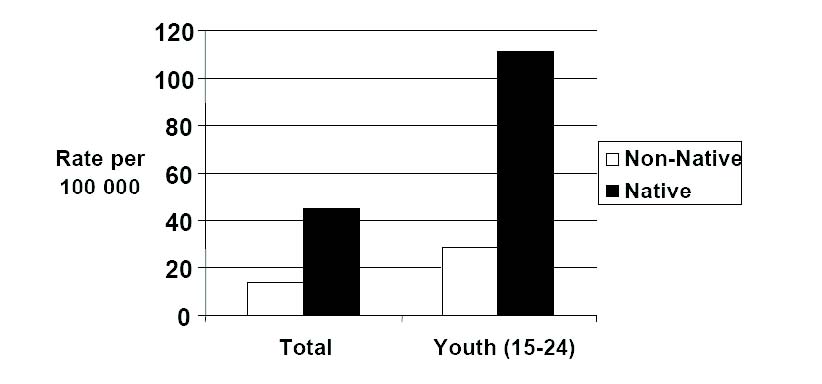

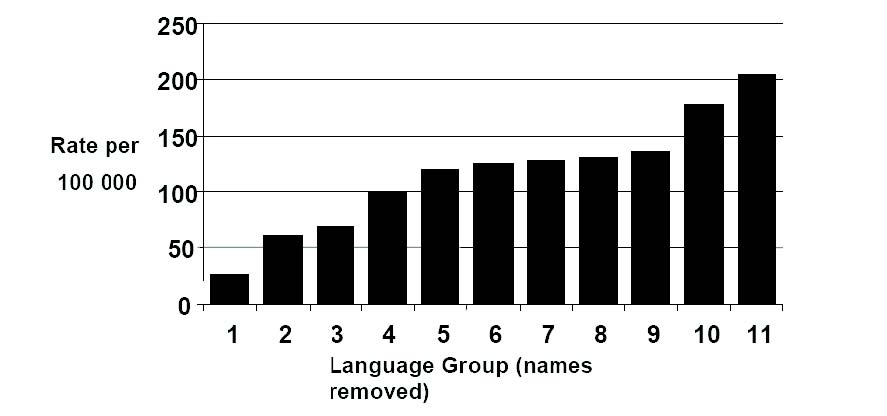

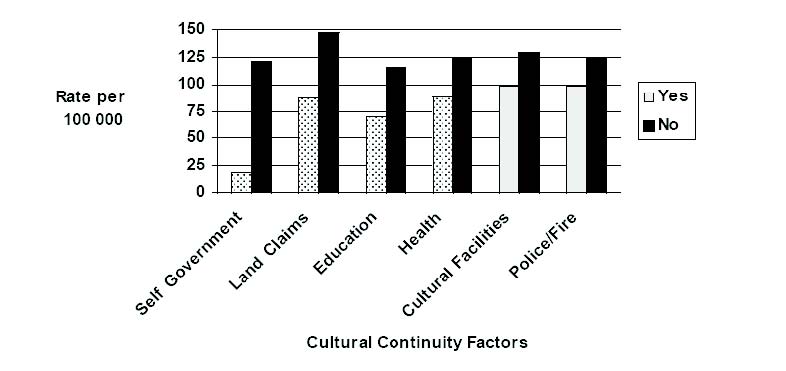

Indigenous suicide in British Columbia (Chandler et al 2003), which has similarities to

Aboriginal suicide (Figure 5) with wide inter-group variations (Figure 6). Michael

Chandler and Chris Lalonde examined six “cultural continuity markers” which might be

understood as autonomous control variables: self-government, land rights litigation,

control over education, health and police, and cultural facilities. For each, suicide rates

were higher for communities without the particular factor than for those where it was

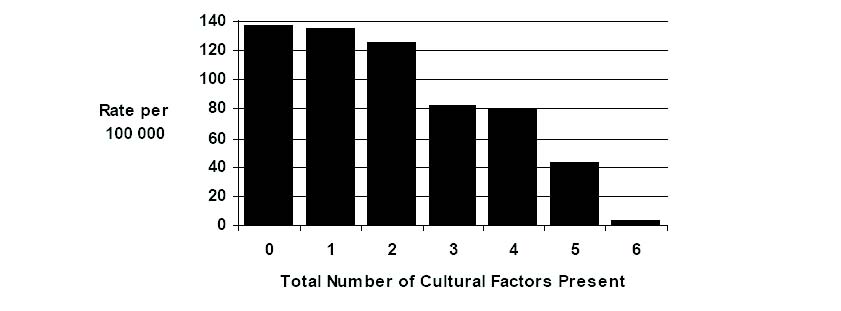

present (Figure 7). However, more startling was the demonstration of a linear

relationship with rates from almost none for communities with all six factors, to nearly

140 per 100 000 for communities lacking any (Figure 8). Further research (Chris

Lalonde, personal communication September 2005) has demonstrated the salience of

two other factors – control over child welfare services and elected Band Councils with

more than fifty percent women.

Figure 5. British Columbia suicide rate (per 100 000), 1987 to 1992

(Chandler et al 2003).

We should not be surprised. “Autonomy is closely linked with self esteem and the

earning of respect”, Michael Marmot (2003:574) insisted, adding that “Both are basic

and … linked. Low levels of autonomy and low self esteem are likely to be related to

worse health”. In 2005, Chris Lalonde visited Cairns and I asked if his research could

be done in Queensland. It can’t. What passes as Indigenous control in Australia is a

veneer, as the demise of ATSIC and the vulnerability of ‘community controlled’ services

attests. As is much of the rhetoric of self-management – as Gaynor Macdonald

(2001:16) aptly observed in relation to remote communities: “People cannot selfmanage

without something to manage. They are managing their own welfare

dependence”. This is, of course, the issue raised in objection to Tony Abbott’s call for a

new paternalism to address the ‘failures’ of ‘self-determination’.

Figure 6. British Columbia Aboriginal youth suicide rate (per 100 000),

by language group, 1987 to 1992 (Chandler et al 2003).

So, for medical professionals and professions, what would it take to support real

autonomy, and, is that precluded by the paternalism that characterises medical

practice? A key question. I have invoked ‘choice’ repeatedly in this presentation.

Autonomy is about the ability to conceive choices and exercise them. Failure to provide

‘choice’ has also been invoked as a criticism of government ‘paternalism’, for instance

in relation to Shared Responsibility Agreements (Collard et al 2005). But choice is also

invoked to the opposite ends, Noel Pearson (ABC TV 2005) commenting that “We first

need to arm young Indigenous people with the ability to choose. And that ability to

choose comes from a proper engagement in mainstream education and a proper

investment in their health, and the proper capacity to choose”. Pearson rejects that this

is assimilation. It is, rather, bicultural empowerment. He also defends assertive

childhood intervention: “I’m prepared to be paternalistic in relation to an early

intervention because the ultimate paternalistic act … is the State stepping in and taking

children away from their families” (ABC TV 2005).

Indeed, he and Pat Dodson (Dodson and Pearson 2004:17) also have noted: “Given

the collapse in expectations, we believe the government has a role in assisting

Aboriginal communities to restore responsibility through mutual obligation” – albeit not

in a manner that further erodes family and community responsibilities.

This is a contested position but, clearly, interventionism and ‘paternalism’ are now on

the national Indigenous affairs agenda. Medical professionals should be involved in that

debate and consider what informs the positions they adopt. We should reflect on the

‘politicisation’ of Indigenous health which, it has been argued, has obstructed

addressing key child socialisation determinants of the persisting Indigenous health

differential (Sutton 2005). On the other hand, we should also resist medicalising social

justice issues, such as of human rights violations into diagnoses which, I contend,

supports victim rather than survivor status. Judgements and actions informed by such

reflection are difficult but necessary. As doctors, caring (and occasionally curing)

involves asymmetrical and thus paternalistic relationships. As it is unethical to ignore

the rights of vulnerable individuals by rigidly invoking a chimera of autonomy or

empowerment paternalism is inevitable in clinical practice.

Figure 7. British Columbia Aboriginal youth suicide rate (per 100 000) by

presence or absence of specified cultural continuity factors in

communities (Chandler et al 2003).

Figure 8. British Columbia Aboriginal suicide rate (per 100 000) by total

number of cultural continuity factors present in communities

(Chandler et al 2003).

At a wider policy and political level, contributing to the creation of autonomy with real

options and choice will also involve paternalism. However, to the extent that medical

professionals and professions contribute to this, it must be through influencing

Indigenous agendas and in support of Indigenous leaders. To that end, as non-

Indigenous professionals we should be engaged through “ethical relationships”, as has

been recommended in terms of a values-based approach to Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander health research by the National Health and Medical Research Council

(NHMRC 2003).

Back to Redfern: atonement and autonomy

To move on requires going back to Redfern – to Keating’s acknowledgement and then

on to the other recommendations of the Stolen Generations Inquiry. Colin Tatz (1983)

anticipated this two decades earlier when he stated that atonement (in the sense of

reparation and reconciliation) demands acknowledgment, restoration – returning what

can be, and restitution – compensation for what cannot. That will be a major issue for

the nation. It may involve a treaty, Indigenous political representation, or sovereignty,

as in Canada, the United States and New Zealand (Hocking 2005). It will entail a cost.

Mindful of Sacher’s assessment that “you have an education problem”, I suggest that

one component should be sustained commitment of sufficient resources to ensure

parity in educational outcomes between Indigenous and mainstream children –

compensation for the violation of past generations by empowering those of the future.

We should note societies, for instance New Zealand and Hawaii, where this has

strengthened culture. It will certainly strengthen Indigenous agency and, ultimately,

Australia. Education is important for health and both are critical to fair equality of

opportunity, but health may be the most potent stimulus for public support and political

will.

I have suggested that in addition to our ‘modest but practical ways’ as doctors, which

we should do well, the ‘middle E’ in relation to Indigenous Australia relates to the

relationship of health and other rights, particularly education. I have also tried to

articulate how I have sought to resolve the tensions between the competing values and

motivations that challenge me in my work – particularly that between supporting

autonomy versus “justified paternalism”. What medical professionals can provide is

theory, expertise, evidence and advocacy. As Robert Beaglehole (2006:260) recently

commented, the critical question for public health practitioners: “is how to build the

social movement to support nascent political efforts to address the unacceptable levels

of health inequalities in all societies”. We should also respond opportunistically to

political winds. For instance, in relation to recent suggestions of “shutting down”

‘dysfunctional’ remote communities such as Palm Island (Anderson 2006; Gerard

2006), or of rationalising economic dependence (Altman 2005), I think that we should

argue that both are unacceptable. Regardless of its obvious problems, so is shutting

down CDEP without alternatives – as is happening now. Rather, policy and effort

should be directed towards enabling choice and providing the means to influence

individual and collective destinies. However that is done, it will demand educational

outcomes. We owe this as a nation and can advance it through health advocacy as a

profession. In practice, I consider that the conflict between actions driven by outcomes

versus autonomy or justice can only be resolved through reflective practice, including

awareness of our capacity to cause harm despite best intentions. The ‘middle E’ will not

be found in inflexible investment in either values or outcomes, but in recognising the

limits of such certainties in the face of social complexity and the need, then, for

reflection-based judgement informed by an awareness of our own limitations.

Australian doctors are almost all non-Indigenous. While with time that will change, I

have avoided the safe option of saying: “it’s not for us to decide”. As doctors we must

make decisions, hopefully based on informed judgements. And while we belong to what

Noel Pearson (2002) calls “the progressive, liberal-minded intellectual middle class”, it

might be recalled that it was from this group that a lawyer, Hal Wooten, and a doctor,

Fred Hollows, thirty-five years ago took a critical look at the performance of their

respective professions in relation to Indigenous Australians and enabled a paradigm

shift with the formation of Indigenous services – in Redfern (Jennett 1999).

Maybe that was their ‘middle E’. Whether or not, they would have agreed with Paul

Keating’s plea in that place twenty years later for imagination and ideals. Finally I leave

you with the words of Nicholas Rescher (1987:83):

The useful work of an ideal is to serve as a goad to effort by preventing us

from resting complacently satisfied with the unhappy compromises

demanded by the harsh realities of a difficult world.

* Professor Ernest Hunter. Professor Hunter spoke at Kos

2007 based on his research work published in AIATSIS

Research Discussion Paper 18, first published in 2006 by the

Research Section Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander Studies, edited by Graham Henderson, Heather

McDonald and Graeme K Ward (ISBN 9780855755522; ISBN 0

85575 552 0) and the paper is reproduced on this CD-Rom of

the Collated Papers of Kos 2007 with the kind prior written

permission of Professor Hunter.

< Return to index |